When was the soap invented tell you

What Is Soap, Officially?

Much of the confusion with the official definition occurs between true soap and synthetic cleansers – what the FDA calls “detergents.” True soap, or ordinary soap, is defined as the “combining of fats or oils with an alkali, such as lye.” Many of those bars on the shelves, and many of those bottles with a pump, aren’t soap at all, but a mix of synthetics, many of them included to offset the essential skin-stripping nature of detergents.

The FDA makes no distinction between soap made with vegetable fats and soap made with tallow. They make no attempt to define organic soap. There’s is a simple task. Even the regulation of soap falls to a different government agency, the Consumer Products Safety Commission. Still, it’s not just ingredients that determine whether a product falls under the regulatory definition of soap. There are two more variables to consider. Here’s a handy three-point definition:

- Ingredients. To be regulated as soap, a product must be composed mainly of the “alkali salts of fatty acids,” meaning what you get when you combine fatty acids with lye.

- How It Cleans. The “alkali salts of fatty acids” must be the only ingredient that provides cleaning action. If added synthetics play a part, the product is no longer soap, but a cosmetic.

- Its Intended Use. To be regulated as soap, a product must be labeled and marketed only as soap. If its intention is to moisturize the skin, deodorize the skin, or make the skin smell nice, it’s no longer soap, but a cosmetic. If it’s intended to treat eczema or prevent disease by killing germs, it’s no longer soap. It’s officially a drug.

When was the soap invented

Records show that soap was produced as early as 2800BC by the Ancient Babylonians, but soap became particularly popular during the Victorian era, when mass production became feasible following the industrial revolution. This combined with a growing understanding of sanitary practises and advertising to encourage bathing with soap, ensured that the humble soap bar fast became an essential household object.

What is the formula for soap

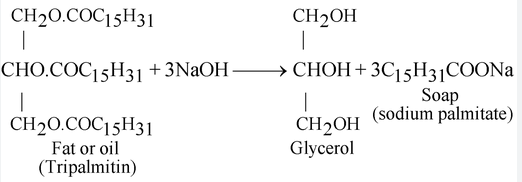

For centuries, humans have known the basic recipe for soap — it is a reaction between fats and a strong base. The exact chemical formula is C17H35COO- plus a metal cation, either Na+ or K+. The final molecule is called sodium stearate and is a type of salt. Depending on the metal cation, soaps are either potassium salts or sodium salts arranged as long-chain carboxylic acids.

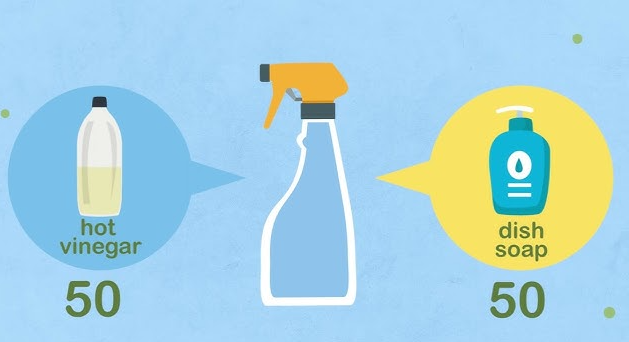

Typically, the formation of these chains involves combining potassium hydroxide with an animal or vegetable fat, or sometimes with acetic acid . A soap molecule does two things — it bonds to both water and debris. That is due to its hydrophilic, or "water-loving," and hydrophobic, or "water-fearing," components. A molecule of soap has a hydrophilic anionic "head" and a hydrophobic "tail" made of hydrocarbons. The head of the molecules is attracted and dissolves in water, while the hydrocarbon tail is attracted to dirt and grease, and repelled by water.

Soap is also a surfactant — it reduces the surface tension of water. Water has a strong surface tension , which causes drops to bead on a variety of surfaces ranging from metal to fabric. That slows water's wetting process and inhibits its ability to clean. Because soaps lessen the surface tension of water, it can spread and wet more easily. Also, surfactants loosen and emulsify dirt and debris, dispersing it in water and allowing it to get rinsed away.

Today, the process of making soap most commonly involves reacting an organic acid with an alkaline chemicals like potassium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide. Industrially, the caustic soda base used most often is sodium hydroxide, which is also called lye. The main difference between potassium and sodium soaps is consistency — usually, potassium makes a softer, more water-soluble soap than sodium.

How Does Soap Work?

Soap is able to clean hands and dishes because of some pretty nifty chemistry. Soap molecules have on one end what’s known as a polar salt, which is hydrophilic, or attracted to water. The other end of the molecule is a nonpolar chain of fatty acids or hydrocarbons, which is hydrophobic—meaning that it’s repelled by water but attracted to grease and other oily substances. When you wash your hands, the soap forms something like a molecular bridge between the water and the dirty, germ-laden oils on your hands, attaching to both the oils and the water and lifting the grime off and away. Soaps can also link up with the fatty membranes on the outside of bacteria and certain viruses, lifting the infectious agents off and even breaking them apart. Once the oily dirt and germs are off your hands, the soap molecules thoroughly surround them and form tiny clusters, known as micelles, that keep them from attaching to anything else while they wash down the drain.